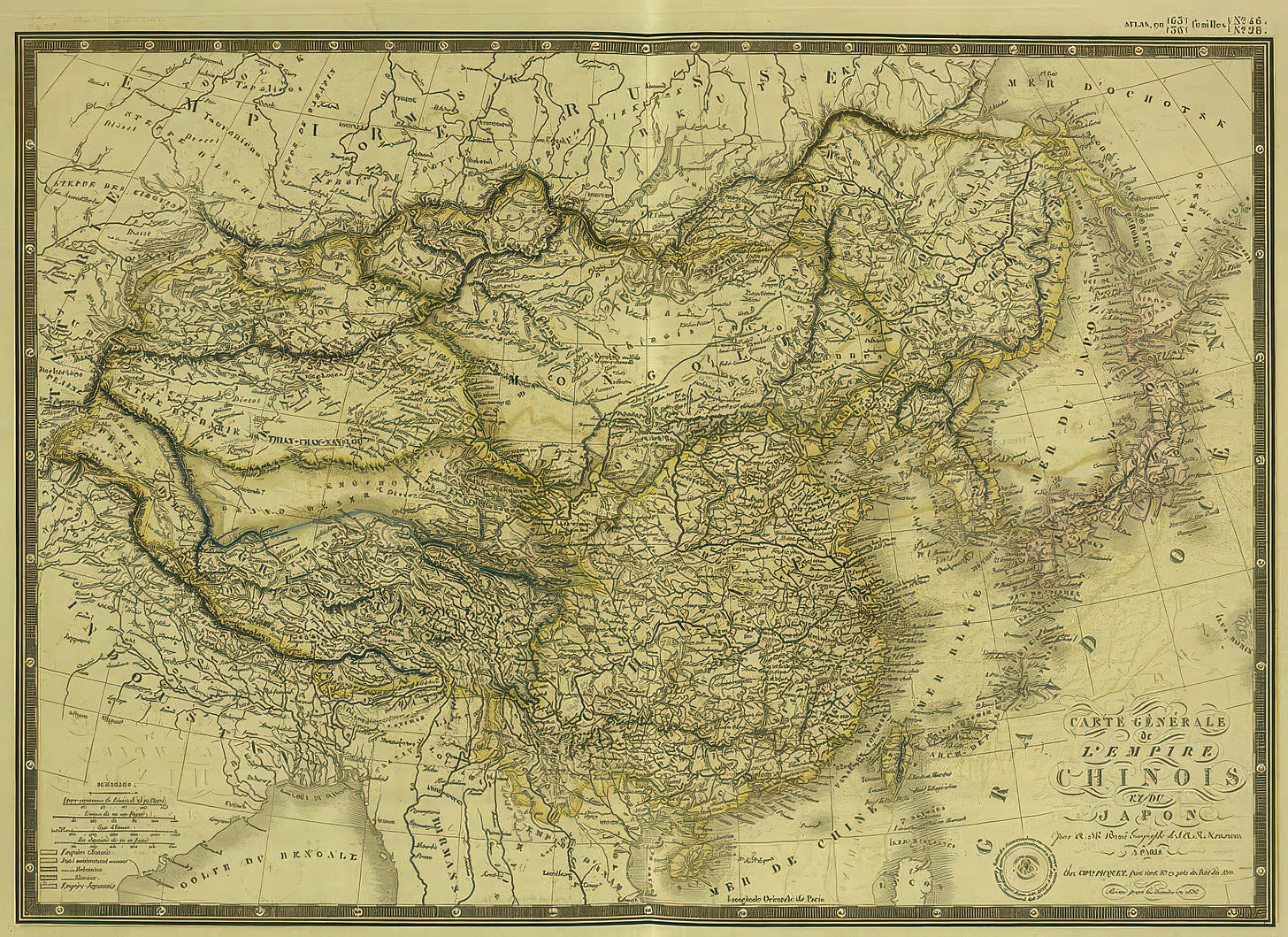

Ancient Doctrine, Digital Tools: China’s Enduring Model for Irregular Governance

How Imperial Statecraft Shapes Beijing’s Modern Approach to Control, Absorption, and Power

When Beijing moves on Taiwan, it is unlikely to improvise post-invasion governance. The Chinese state appears positioned to apply strategic principles refined over more than two millennia, recently field-tested in Xinjiang, and now scalable through modern technology.

Western analysis often treats China’s irregular warfare toolkit—surveillance, lawfare, demographic engineering, narrative control—as novel products of Xi-era authoritarianism. This framing misses the deeper pattern. The tools are modern; the governing logic reflects much older traditions.

China’s approach to Xinjiang, Taiwan, and Belt and Road partner states appears to follow enduring strategic principles inherited from imperial statecraft. The tactical implementations are modern—AI surveillance, global infrastructure investment, real-time social control. But the strategic logic suggests continuity with ancient methods: comprehensive absorption through legal, economic, demographic, cultural, elite, and informational domination.

This distinction matters because Beijing appears to have inherited proven strategic principles and upgraded them with 21st-century tools. Understanding this reveals three urgent realities: Xinjiang likely reflects doctrinal application developed over time. Taiwan may face the application of tested strategic principles shaped by historical precedent. This governance model appears structured for global export. Irregular governance doctrine refers to long-term population control methods designed to absorb, reshape, and manage contested regions without requiring continuous large-scale kinetic force.

This isn’t a prediction of inevitability, but a warning that historical patterns may shape how Beijing plans, sequences, and measures success after force is used.

Why This Framework Matters Now

Current intelligence collection may be misreading Chinese actions as reactive authoritarian overreach rather than systematic doctrine implementation. This analysis gap produces three recurring analytic blind spots. First, intelligence priorities may be misdirected as analysts track individual tactics without recognizing the integrated strategic framework connecting them, fragmenting threat assessment and missing operational patterns. Second, analysts may misinterpret tempo and sequencing because democratic systems assume gradual escalation allows time for response, while generational transformation campaigns operate on fundamentally different timescales. Lastly, resource allocation may follow the wrong threat model, with current approaches countering individual tools rather than integrated systems, potentially wasting limited resources on symptomatic responses while underlying strategic frameworks advance.

There are two possible explanations for the observed continuity. The first is deliberate doctrinal inheritance: that Beijing has consciously studied, retained, and adapted imperial statecraft principles for modern governance and irregular warfare. The second is structural recurrence: that centralized authoritarian systems independently converge on similar methods when governing contested populations, regardless of historical memory.

Distinguishing between these hypotheses matters less than their analytical consequence. In both cases, intelligence collection and planning must assume continuity until disproven. Treating these patterns as improvised preference rather than repeatable doctrine risks systematic misreading of intent, sequencing, and success metrics.

Six Tools, Two Millennia: How Ancient Statecraft Operates at Modern Scale

China’s irregular warfare toolkit appears to reflect six recurring mechanisms that have persisted across dynasties while adapting tactically to technological change. Understanding this continuity may explain why Western analysts consistently misread Chinese actions as improvised authoritarianism rather than systematic doctrine implementation.

1. Legal Domination: Make Resistance Legally Incoherent

The Qin Dynasty standardized laws across formerly independent states in the 3rd century BCE, making local customs illegal and imperial authority the only legitimate source of order. The Qing systematized this approach in 18th-century Xinjiang, imposing regulations that outlawed traditional governance structures.

Today’s “counter-extremism” regulations in Xinjiang follow similar logic with enhanced precision. Religious practice becomes criminal extremism, traditional dress becomes radicalization indicators, and language preservation becomes separatist activity. Taiwan already faces early-stage implementation through Beijing’s “Anti-Secession Law,” which pre-criminalizes democratic processes as illegal secession. If Beijing initiates force, the legal framework for mass detention appears largely prepared in concept and form.

2. Economic Dependency: Bind Peripheries Through Structural Integration

Han and Tang military-agricultural colonies offered economic privileges that bound settlers to imperial infrastructure. The Qing refined this through migration incentives and state monopolies that made economic independence difficult for local populations.

Modern “poverty alleviation” and BRI investments appear to follow similar strategic logic. Xinjiang’s economy now depends structurally on central government transfers and Han-managed enterprises. BRI projects from Pakistan’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port appear to replicate this pattern—Chinese investment creates dependency relationships that may constrain recipient sovereignty.

3. Demographic Engineering: Change the People, Change the Problem

Imperial military colonies systematically moved Han populations into frontier regions to dilute ethnic concentrations. The Qing increased Han presence in Xinjiang from negligible to substantial within generations through controlled migration.

According to Chinese census data, Xinjiang’s Han population increased from 6% in 1953 to over 42% by 2020 through hukou system controls, economic relocation incentives, and concentrated infrastructure development. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps functions as a modern equivalent of Han Dynasty military colonies. This pattern appears globally wherever Chinese investment concentrates, with BRI infrastructure projects frequently including worker housing that becomes permanent settlements.

4. Cultural Replacement: Education, Ritual, Identity

Imperial examinations and Mandarin literacy requirements forced local elites to choose between cultural distinctiveness with marginalization or cultural assimilation for power access. “Sinicization of religion” programs in Xinjiang appear to follow this playbook through Mandarin-only education, patriotic curriculum, and boarding schools that separate children from families.

The key analytical insight involves identifying which cultural practices are celebrated as “authentic tradition” versus redefined as “extremist deviation.” This reveals the target identity Beijing appears to want to construct while eliminating practices supporting autonomous cultural development.

5. Elite Co-option: Convert or Neutralize Local Leadership

The Tusi system granted local chieftains imperial titles and privileges in exchange for accepting imperial oversight, converting resistance leaders into system administrators. United Front work, model citizen campaigns, and religious leaders required to demonstrate “patriotic” loyalty represent technologically-enhanced versions of this logic, now monitored through social credit scoring.

Elite co-option appears designed to eliminate resistance before it can organize. Tracking which local leaders appear in state media as “model” representatives versus those facing harassment reveals which types of leadership Beijing considers co-optable versus threatening.

6. Information Control: Ritual, History, Narrative Dominance

Imperial rituals and court-sponsored histories naturalized the center’s superiority and legitimacy, making resistance conceptually incoherent. China has established nearly 500 national “patriotic education bases“ that propagate official narratives, while external propaganda operations work to establish Chinese historical narratives internationally.

Those who control historical narrative control what populations can imagine about legitimate political organization. Tracking which narratives are promoted versus suppressed reveals Beijing’s strategic messaging priorities.

What’s Qualitatively Different: Scale, Codification, Export

Three changes appear to transform ancient strategic principles into modern irregular warfare doctrine. Technological scale now enables real-time governance through AI-powered surveillance that monitors 20+ million people with precision impossible for Qing administrators, flagging potential dissent before it manifests.

Where imperial control once depended on talented administrators adapting principles locally, modern irregular warfare operates from documented playbooks that can be published, taught, and refined for export. Most significantly, BRI packages surveillance technology exports with “governance innovation” seminars, selling facial recognition systems to over 80 countries while providing diplomatic cover for adopting similar approaches.

Where the Model Faces Limits

Historical precedent—from Han and Tang frontier colonies to Qing administration in Xinjiang—suggests three enduring friction points. First, the model demands sustained state capacity over time, requiring large bureaucratic, fiscal, and surveillance resources. Second, it must continuously suppress low-level resistance, which can impose cumulative security and legitimacy costs. Third, long-term control depends on continued economic expansion to finance incentives, surveillance, and infrastructure; any slowdown increases risk to both compliance and narrative credibility.

These limits do not negate the model’s effectiveness, but they define where external pressure or internal shocks could have disproportionate strategic impact.

Strategic Intelligence Implications

Western analysis often treats Xinjiang as an overreaction to terrorism, potentially misreading systematic application of refined statecraft. Terrorism provided justification; the strategic logic appears to have been developed independently as doctrine.

Similarly, many indicators suggest Beijing may assess Taiwan not in terms of “if,” but “when” conditions align for preferred timing. CCP post-invasion governance likely reflects systematic implementation of tested methods, with legal frameworks for criminalizing resistance, economic systems for creating dependency, and surveillance infrastructure for comprehensive monitoring already existing in documented form.

Meanwhile, “development” appears to operate as strategic deception, with BRI functioning as a comprehensive framework for binding partner states through dependency relationships that may constrain sovereignty without requiring force.

Critical Intelligence Gaps and Collection Priorities

Priority collection requirements should target legal framework analysis, monitoring legislative changes that criminalize cultural practices particularly in contested regions and BRI partner states.

Economic dependency mapping must assess structural economic relationships rather than project-level benefits, modeling scenarios where BRI recipients attempt autonomous policy-making that conflicts with Chinese interests.

Demographic trend analysis should monitor worker visa issuance patterns and permanent residency applications within 50km of major BRI infrastructure sites.

Elite network tracking can map local leadership co-option versus neutralization patterns, while narrative warfare monitoring should track educational curriculum changes and historical narrative promotion in target regions.

The Structural Mismatch

The central challenge involves sustaining democratic institutions capable of competing with systems refined over millennia. Beijing plans for generational transformation; Washington plans for election cycles.

Effective competition therefore depends on building institutions that can operate coherently across decades, not administrations.

If the PLA crosses the Taiwan Strait, it will be carrying a 2,000-year-old manual, tested in Xinjiang and refined through global implementation. Democratic responses require matching this historical depth with institutional commitment to sustained strategic competition. The window for developing these capabilities is measured not in news cycles but in the time required to build institutions capable of generational strategic patience.

Strategic competition with a state that plans in dynastic time horizons requires sustained analytical frameworks and institutional continuity beyond election cycles. Beijing is executing a model refined, tested, and now scaled for modern conditions.